by Killian Quigley

Published by Yale University Press, 2015 | 88 pages

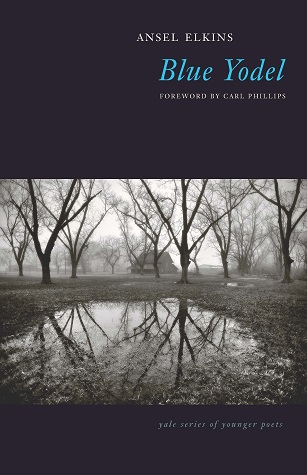

“I tore myself out of my own mother’s womb,” writes Ansel Elkins in Blue Yodel, winner of the 2014 Yale Younger Poets prize. Suffused with this kind of otherworldly violence and loneliness, the poems of Blue Yodel – Elkins’ first published collection of poetry – are solitary vignettes from a dark Southern dystopia. Though told mostly in the first-person, these poems are hardly “spoken” at all, their diverse voices appearing as isolated and ghostly utterances of multiple, shrouded personas. Lines here howl past each other in the dark – bare-boned, spectral, like Jungian archetypes or tarot cards. The titles Elkins has chosen – “The Girl with Antlers,” “The Lighthouse Keeper,” “Werewolf in a Girl’s Dormitory,” etc. – only reinforce this effect, enveloping Elkin’s collection in an air of dark surrealism.

Blue Yodel springs from the landscape and vernacular of the American South, in particular the southern gothic literary tradition. The book begins with an epigraph from Zora Neale Hurston, in which Hurston details her initiation ceremony under Luke Turner, the nephew of Marie LeVeau and himself a hoodoo doctor in New Orleans: “A pair of eyes was painted on my cheeks as a sign that I could see in more ways than one.” Blue Yodel’s poems share that tradition’s interest in death and spiritual power. Elkins further imbues her lines with biblical cadences, imagery and characters, deployed here, however, to more secular, perhaps psychoanalytic purposes.

Elkins often weds these poems’ apocalyptic eschatological tendencies with Southern musical forms. “Blues for the Death of the Sun,” the poem that opens Blue Yodel, speaks of a land where the sun goes dark and the earth is bathed in night: “We saw the sun vanish. / Like crows, the people of my town pace the streets, faces skyward. / From wet ground ferns spring, fronds greening with hunger.” Another poem, “Devil’s Rope,” inspired by Cousin Emmy’s rendering of the country ballad “Ruby,” revises the ballad and imagines a darker infatuation and a more daring lover: “I killed our ancient blue rooster and buried / his singing beak in the garden while you slept, before that devil / could disturb your slumber to report that dawn.” Elkins here reconfigures the blues as an elegy for environmental destruction, the final thoughts of a planet doomed to extinction. In the calmness of their tone, despite the imminence of their sense of impending doom, Elkins’s speakers recall the character of Justine in Lars von Trier’s Melancholia.

Just as the Southern voices in her poems remain detached in the face of unordinary calamity, Elkins astonishes with transformation of the ordinary into the surreal. In “The Girl with Antlers,” the reader encounters a girl born with antlers who passes the time reading by a fireplace. In “The Lighthouse Keeper,” the speaker cages and chains a fallen angel to his radiator. “I aimed a rock at the back of the angel’s head / and hit him. He fell.” The speaker rarely interacts with his imprisoned angel over the course of the poem, except for a nursery song the keeper occasionally sings to his captive. By the end of the poem, God has still failed to reclaim his fallen creature:

At dawn the angel watches the fishermen depart

in battered boats. Wings spread wide

as a buzzard’s

he suns himself by the window

and keeps ceaseless watch

over the empty harbor at low tide,

the sky absent of all but the crying

gulls as they coast on invisible wind.

Elkins here forcefully contrasts the imprisoned angel, its wings now useless, with the ordinary gulls that skip and soar over the water’s surface.

Despite their varied speakers and themes, almost all of Elkins’ poems are imbued with a sense of effacement and solitude. In “Sailmaker’s Palm,” the speaker’s chronicle proceeds—more or less unruffled—from before his death, through his death and into the afterlife, where he remains his usual self, solitary and stitching sails for a living:

When a sailor dies at seathe ship’s sailmaker sews the dead man into a canvas shroud.Stitch by stitch, the sailmaker closes him tightly roundwith twine; he works his way from foot to head.And the last stitchhe sews through the dead man’s nose.

Death, Captain,is not what I feared it would be.I was blown through death.Death blew through me.I was sewn into the wind itselfas a singing voice blown out to sea.

Even in poems such as “Adventures of the Double-Headed Girl,” which, as the title suggests, begins with a two-headed speaker (“We are indeed a strange people / wedded together, axis of a shared spine”)—one of the speakers quickly takes over the narrative with a wraithlike singularity: “is he flirting with me or you? I reply with a kiss blown / from my tight-gloved hand.” Elkins seems to suggest that our nature as human beings somehow makes us incapable of sustaining unity, of achieving true solidarity with others.

Throughout Blue Yodel, Elkins repeatedly returns to the nature of the past, of memory and regret, and of things that cannot be undone. In “Reverse: A Lynching,” Elkins desperately tries to turn the wheels of time back: “Return the tree, the moon, the naked man / Hanging from the indifferent branch / Return blood to his brain, breath to his heart / Reunite the neck with the bridge of his body.” The repeated imperatives manifest the speaker’s desire to undo the horror of racial violence, recollected or witnessed through the historical record like a film being rewound but that return to grace remains elusive. In Blue Yodel, the darkness of the past bleeds into the present and yet the present, too, shapes the memory of past beliefs, resurrecting the centrality of fear and belief. In a brief moment of hopefulness, Elkins reminds us of our potential as created beings, of our belief we “are fearfully and wonderfully made.”

Ayten Tartici is a PhD candidate in Comparative Literature at Yale University.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig