by Angela Moran

Published by New American Library ; Basic Civitas Books, 2010 ; 2008 | 672 ; 320 pages

Hip-hop can’t seem to escape its own history, and that’s probably a good thing. Two recent books on this multifaceted art form and its broader reverberations in American culture trace hip-hop’s path through the postindustrial twentieth century and into the twenty-first, as a means of understanding it in the present day—and, crucially, using this understanding to make claims about what hip-hop will be in the future.

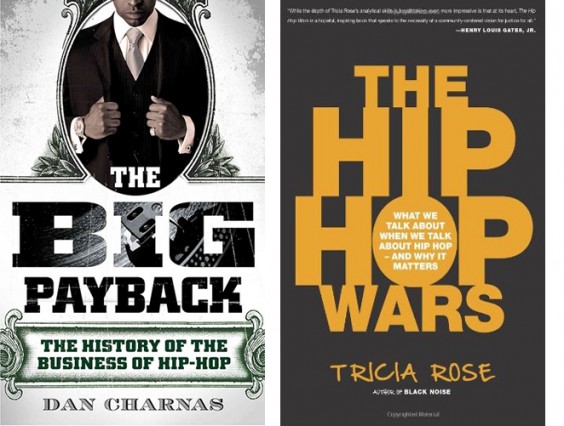

Dan Charnas’s The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop is a hefty volume, meticulously researched, chronicling the now nearly four-decade-long history of hip-hop by tracing the money: a productive lens that lets Charnas examine the various relationships and institutions that have made hip-hop possible and shaped its direction through the years.

Tricia Rose’s The Hip Hop Wars: What We Talk About When We Talk About Hip Hop—and Why It Matters is an incisive commentary on, well, exactly the debates referred to in her title. Rose lists the “top ten debates in hip-hop” and then elegantly dissects each one, bringing the lengthy and intertwined histories of hip-hop, American race and class dynamics, and late twentieth-century media and corporate practices to bear on each debate. Her careful analyses point the way forward for a progressive reimagining of hip-hop, one that Rose believes to be truer to the better angels of hip-hop’s nature than aspects of our current musico-political climate.

The Big Payback, at nearly seven hundred pages, fills important gaps in the literature on hip-hop, which has previously attended primarily to musicians, fans, and cultural politics. The rise of gangsta rap in the early 1990s, the prominence of bicoastal beef through at least the early 2000s (the best example of which is the feud resulting in the twin shootings of rappers Tupac and Biggie in 1996 and 1997, respectively), and the turn-of-the-century emphasis on bling—to give just a few instances of extremely important developments in hip-hop’s history—are well-explained here through the lens of corporate power.

The existing hip-hop literature tends to point the blame for developments perceived as negative at the vague specter of mass media and corporate power, as in Jeff Chang’s well-respected, yet flawed, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation (St. Martin’s Press, 2005). Although this perception is not entirely untrue in many cases—certainly record labels would have clamped down on East Coast/West Coast feuds more quickly had they not been so lucrative—Charnas complicates the picture and shows that hip-hop artists, for better or worse, had a more active role in creating hip-hop’s present state than is often casually assumed. There’s no conspiracy here—just a lot of people trying to get paper, sometimes (often?) without much concern for the ethical or social implications of how they do so. Hip-hop, as it turns out, is a job a lot like any other.

The Big Payback is chatty, casual, and relies for the most part on snappy narration and reconstructed dialogue. I ain’t hating, but this was my least favorite aspect of the book. On one hand, Charnas’s style made it easy and pleasurable to get through the hundreds of pages between the book’s money-green covers; on the other, it made it very difficult for Charnas to take a step back and analyze the implications of the events he describes.

I share his admiration for the hustle that enabled many of these artists and businesspeople to get to the top. But what are the consequences of some of these trajectories? Anyone who follows the news can probably think of a few without much effort, and I would hope that anyone who loves hip-hop as much as Charnas evidently does would offer more constructive critique along with praise.

Furthermore, Charnas has access to this wealth of casually offered detail due to his own history in the hip-hop business as a journalist, scout, and promoter for major rap labels. Yet he is curiously almost absent from his narrative. I like to know where authors are coming from, and a more explicit acknowledgment of his history would clarify his perspective, allowing readers to make more informed judgments about the few editorial observations he offers.

Nonetheless, The Big Payback is a monumental and long-overdue contribution to the literature on hip-hop, and I sincerely and fervently hope that Charnas’s narrative, and careful attention to the Benjamins, will be integrated into our common-sense histories of hip-hop.

Rose’s Hip Hop Wars addresses the ethical dimensions of the cultural politics of hip-hop—largely absent in The Big Payback—and provides a compelling reimagination of hip-hop’s future. Rose is perhaps the preeminent American scholar of hip-hop, and her perspective is the result of decades of experience with and deep thought about the art form, from many angles. The Hip Hop Wars is her second book explicitly about hip-hop, following up on her game-changing Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Wesleyan University Press, 1994).

Black Noise traced hip-hop’s first fifteen or so years; in The Hip Hop Wars, Rose assesses all that has happened since then and critically reflects on its implications. Her central contention is that the American national discussion about hip-hop addresses racial tensions and issues that we otherwise choose to avoid. Her preface sets the agenda for the book: Rose writes, “Hip hop is not dead, but it is gravely ill. The beauty and life force of hip hop have been squeezed out, wrung nearly dry by the compounding factors of commercialism, distorted racial and sexual fantasy, oppression, and alienation.” Yet Rose is no nostalgist; she confronts hip-hop’s history, especially its recent history, with clear-eyed realism, which gives her analyses and proposals for change all the more intellectual and ethical force.

Rose frames the national discussion around hip-hop in a list of ten debates, five each from hip-hop’s critics and defenders. She then takes each to task, exposing the underlying dynamics of racism, classism, and sexism in each contention and proffered defense. Though Rose is, of course, an ardent hip-hop fan, she believes that those who truly love hip-hop should constructively criticize where necessary. Thus, she suffers no foolishness from either side.

What does this look and sound like? Rose sets out six guiding principles for progressive, ethical creativity in hip-hop. First: “Beware the manipulation of the funk.” Don’t support music with unacceptable lyrics even when the beat is infectious. Second: “Remember what is amazing about chitterlings and what isn’t.” Part of what Rose identifies as the “genius of black creativity” is the ability to make something out of next to nothing. But this shouldn’t be accepted as a pass when the fruits of that creativity are poisonous. Third: “We live in a market economy; don’t let the market economy live in us.” Rose accepts that participation in the capitalist economy is essentially inevitable, but she exhorts us to consume wisely and with our values in mind. Fourth: “‘Represent’ what you want, not just what is.” Rose argues that artists should represent their hopes, goals, and dreams along with their harsh truth-telling about today’s hardships. Fifth: “Your enemies might be wrong but that doesn’t make you right.” She exhorts hip-hop’s supporters not to waste energy in responding defensively to misguided attacks, but rather to develop internal critiques based in love and respect. Sixth and finally: “Don’t settle for affirmative love alone; demand and give transformational love.” The latter form of love enables both straightforward praise and constructive critique.

The Hip Hop Wars is an important intervention into our interrelated national debates on hip-hop and race. Rose’s eloquent third way, between haters and misguided lovers, is a workable blueprint for reshaping hip-hop into forms that will support equality, respect, dignity, and honesty.

Hip-hop has made an immense global impact, in realms as diverse as popular music and fashion, food and race relations, business and entrepreneurship, visual arts and dance, television and media distribution, poetry and narrative, and even national and international politics. It’s vitally important that intellectual reflection and analysis do its best to keep up with hip-hop’s protean energy, to help us make sense of our world in hip-hop, and to keep our national and international discussions on a constructive path. These two books, along with the recent efflorescence of smart and nuanced discussions of hip-hop culture in various forms, are important contributions to this process.

Meredith Aska McBride is a Chicago-based ethnomusicologist, writer, violinist/violist, and music teacher. She is a graduate student in ethnomusicology and Jewish studies at the University of Chicago, and is on the faculty of the Hyde Park Suzuki Institute. Her previous writing has appeared in Philadelphia Weekly, Next American City magazine, and the Daily Pennsylvanian.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig