by Mark Molloy

Published by The University of North Carolina Press, 2016 | 226 pp pages

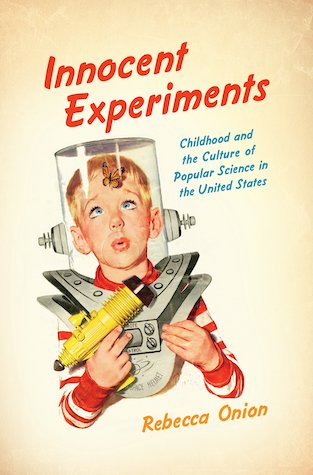

Most of us know Neil Armstrong’s iconic words after he landed on the moon on July 20, 1969: "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind." The line perfectly captured the magnitude of the feat and the worldwide impact it had. The quote suggests, however, that the contribution to “mankind” was egalitarian and unselfish. The reality of the matter, of course, is more complicated. The moon landing was fraught with international tensions and competition, conspiracy theories, and cultural division. The famous quote romanticized scientific progress as a unifying force in a time of political division. The title of the book Innocent Experiments—Rebecca Onion’s exploration of the history of science education in the twentieth century U.S.—contains a similar contradiction. Onion proves throughout the book that science education has been anything but innocent, despite attempts to market it as such. She depicts the contextualized history of science education as political and ideological, with racist, sexist, and classist tendencies that persist today.

For the vast majority of human history, scientific and technological progress was slow and incremental. Phenomena were noted, but no rigorous methodology existed to guide the path to learnings. This began to change around the turn of the seventeenth century, with the implementation of the scientific method via the writings of Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626), Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642), Johannes Kepler (1571 – 1630), and René Descartes (1596 – 1650), and was given a massive boost with the 1687 publication of Isaac Newton's Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which firmly established science as a mathematical, quantitative field. After this, progress accelerated exponentially, reflected not only in theoretical advances but also in the emergence of the European industrial revolution of the eighteenth century. Suddenly the caliber of a nation’s scientists and mathematicians could be directly tied to the standing of that nation on the regional or even global scale. Governments, unsurprisingly, took note, and implemented the modern popular scientific education.

Onion’s study picks up in the early decades of the twentieth century, when popular science education was still in its infancy in the US, and some of the earliest science educational opportunities to the average family were via chemistry sets that could be purchased at the local toy store. Early popular ‘educational’ materials and scientific communications frequently reached beyond the domain of pure science to appeal to the consumer’s fantasies and desires. Early inceptions of scientific education via chemistry sets—beginning roughly in 1918, and directed almost exclusively to young, white, middle-class boys—bore echoes of magic and alchemy while selling the appeal of performance and mastery over an audience. With a chemistry set, the young alchemist could possess the power of magic and science in his own basement or clubhouse, and could socialize with other young scientists like him. As a result, chemistry clubs became popular in the 1920s and remained so for the next few decades. Companies’ marketing efforts were focused less on the chemistry sets they were selling, and more on ideals that appealed to parents and young boys alike: these chemistry clubs were “a way to learn group dynamics and managerial strategies, as well as science,” read one early marketing pitch. The young chemist could become a group leader, and could mesmerize audiences with pseudoscientific magic shows. One of the most popular companies, A.C. Gilbert’s Chemcraft, encouraged boys to purchase their products as a means of worldly advancement through an eventual career in science.

These advertisements and educational materials, not surprisingly, either obscured or condescended to children of color and girls. Onion includes a shocking example of a 1937 Chemcraft manual that—within its instructions--encouraged boys to procure an assistant or apprentice for their shows: another boy in blackface who would be named “Allah, Kola, Rota, or any other foreign-sounding word”; Onion describes how the rest of the instructions suggest that the apprentice should be called “slave.” While children of color were rarely represented in the realm of science education, and when they were they were horribly demeaned, young girls were given a supportive role, staged as passive observers interested only in beauty or pleasantry, and not the least bit in the scientific workings of reality. When, in the course of his important work, the budding male scientist made a mess, his mother or admiring girl would be there ready to swoop in and clean it up. Public health organizations such as the National Safety Council (NSC) warned women to avoid injuring themselves when around young boys’ hazardous experiments, which, it was assumed, they would be unable to understand.

In the middle decades of the twentieth century scientific development and education grew as a national concern, and popular science education was prioritized accordingly. During the Second World War, science had the technology it made possible had provided an overwhelming display of its power and worth. In the Cold War with the Soviet Union that followed, government officials and educators feared that the U.S. was falling behind in science education after the USSR’s early victories in the space race. The space race reignited a national preoccupation with science and gave the nation something to strive toward. The promise of space and the threat of falling behind comprised much of popular culture themes, and adults as well as children were immersed in space race rhetoric. Advertisements for telescopes and other space-related gear could be found everywhere.

This national preoccupation with scientific progress, Onion argues, helped democratize science education. Science Service — an organization created by scientists and science-minded journalists that maintained Progressive ideals, believing that science was for everyone, launched the Science Talent Search (STS), which originated out of the desire to promote science to the masses and opened opportunities for girls and minorities to participate in the field. The notion of the STS arose during conversations between Science Service director Watson Davis and G. Edward Pendray of the Westinghouse Electric Company, when they were planning the 1939 World’s Fair. At the World’s Fair, several thousand boys and girls had a chance to display their science talents.

And yet, unsurprisingly, the democratic mission of the Science Service and its talent search was undercut by the realities and politics of the time. The STS was nominally open to all races, but Onion describes how African American participants were rarely present in photographs in the 1940s and 50s. Alabama, a segregated state, separated its black participants from their white counterparts for dinners and scholarships. Young women were allowed to compete and participate, but the rhetoric around female science students remained gendered and sexist, suggesting that female scientists could maintain their sexual appeal and abilities as homemakers despite their smarts. Surveys during these times found that most female participants and winners eventually left the sciences and became homemakers.

Regardless, with the growth of scientific development and education as a national concern, on the whole, companies and institutions worked rigorously to normalize, popularize, and instill interests in science. Schools too sought to encourage scientific interests, trying to tap into young scientists’ curiosity and wonderment. While pulp fiction had been popular among young boys since the 1920s, and resisted by educators, science fiction books were embraced by librarians and educators by the 1950s as a more credible genre. Science fiction became an official sub-category of young-adult fiction, and promised to engage children in science early, and beyond the classroom. Exploratory museums similarly promoted scientific liberation and childhood play outside of school walls: in fact, legions of museums and science centers opened their doors during these years to promising students of science, while postwar rhetoric praised “science talent” and organizations recruited youngsters to publicly demonstrate their scientific acumen.

The push for science education had lost some wind by the late 1960s, and faced resistance by a growing anti-war, anti-government counterculture. The youth movement of the 1960s launched critiques against science as a tool of the war-mongering, capitalist machine. In 1960, Paul Goodman wrote his polemic Growing Up Absurd: Problems of Youth in the Organized System, which argued that the corruption of the Cold War had extended to space exploration. By 1970, the year after the moon landing, the space race no longer caused the fervor it once did. Onion describes evidence that 1970s children were scared of nuclear war and ecological destruction. Pollution was a significant concern, and much of the emerging science fiction included foreboding premonitions and characterized science in a villainous role. More generally, Americans were increasingly unmoved by big symbolic acts of technological or scientific progress. As, of course, they remain today.

Throughout Innocent Experiments, Onion’s historiography is a marriage of thorough archival research and social critique. Onion depicts the influence of popular culture and media within the larger context of political and governmental interests. She traces the proliferation of children’s science education chronologically, beginning with the founding of the Brooklyn Children’s Museum in 1899, moving to the popularization of chemistry sets and other science related toys and activities, and finally ending with the 60s and 70s debates surrounding STEM politics that continue to this today. Throughout the study, Onion carefully documents her claims, including with images of children’s science education materials throughout time, including historical photographs, magazine covers, science kit advertisements, and toy brochures.

Interestingly, Onion’s study begins not in the past but in the recent present. She opens the book with a 2012 photograph of then-President Barack Obama hosting a science fair at the White House. His expression while trying out a young boy’s “Extreme Marshmallow Cannon” is one of pure glee, and his speech at the event heralded the love of science as an American tradition. While the path has been far from direct, Onion’s historiography paints a picture of slow progress over the past century toward a more democratized education for children – all children – interested in science. Still, as evidenced by the continuing disparity in STEM fields among men, women, and people of color, however, that American tradition has not welcomed everyone. Onion’s study is a detailed and comprehensive history, but—perhaps more importantly—a reckoning with the darker realities that lie beneath the patriotic and nationalistic rhetoric of science and technology. Just as recent critical theory has challenged the positivity and objectivity of scientific inquiry and representation, Onion puts the seemingly pragmatic history of science education under the microscope.

Deborah Harris is a Continuing Lecturer in the Writing Program at University of California, Santa Barbara. She is the author of Media and the Rhetoric of Body Perfection (Routledge, 2014) and her research includes medical rhetoric, materialist rhetoric, popular culture, and composition pedagogy.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig