by Erin Becker

Published by Duke University Press, 2020 | 326 pages

If anyone deserves the opportunity to pen a memoir, Margaret Randall does. Randall’s life has included such varied and fascinating episodes as smuggling contraceptives into fascist Spain following an attempt to journey by scooter across postwar Europe and India with an impractical first husband; palling about with Elaine de Kooning and the Abstract Expressionists in the Downtown Manhattan art scene of the late 1950s; moving to Mexico City as a single mother in 1961, where she co-founded and edited El Corno Emplumado, possibly the most important poetry magazine of the 1960s; covertly fleeing to Cuba with her four children following persecution by the Mexican government for her support of the mass protests that seized Mexico in the lead-up to the 1968 Olympics; penning journalism and publishing translations that have offered a first-hand window into everyday life in post-revolutionary Cuba after spending the 1970s living and working in Havana; collecting significant oral histories from women involved in the Sandinista movement in Nicaragua following the successful 1979 revolution; returning to the U.S. in 1984 and waging a successful five-year legal battle against the U.S. government for reinstatement of her citizenship; embracing her lesbian identity and finding a lifelong love; while publishing over one hundred volumes of poetry, oral history, essays, and translations along the way. It’s a terrific and at times terrifying reminder of everything that a person can accomplish in a single lifetime.

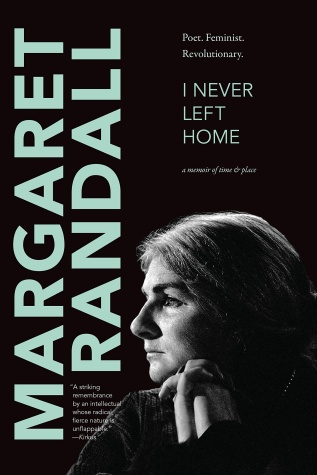

In her new memoir, I Never Left Home, Randall gathers her reflections on each of these periods in her life. More than simply a narrative of her life, however, Randall has written what she describes as “a memoir in which time and place were the central protagonists.” In more concrete terms, I Never Left Home carefully tracks the relationship between Randall’s life and the contexts that shaped and motivated the many twists that her biography takes. These contexts include both an extensive inventory of all of the friends and peers that surrounded Randall and, with an eye toward a critical self-accounting, the dominant cultural norms that consciously and unconsciously shaped her responses to the changing world around her. Randall accomplishes the latter task with a brutal honesty, whether she is remarking on the early traumas and unspoken desires buried beneath her parents’ dedication to maintaining appearances, reflecting on the lack of feminist consciousness in her work before the 1970s, or commenting on the “racist conditioning” that stoked her own uncomfortable fears as a child.

Randall divides I Never Left Home into chapters largely defined by her place of residence: the suburbs of New York City, Albuquerque, Lower Manhattan, Mexico City, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Albuquerque again. The book proceeds somewhat episodically, especially in its earlier stages, as Randall notes that “the connective tissue” of these years, stretched and fragmented, has left behind only disconnected “islands of experience.” Randall adds to this episodic structure by punctuating the book with what could amount to a modest Selected Poems, performing a complex layering of time, as each poem adds another dimension to the incident being narrated, but reframed through the perspective of the time of the poem’s composition (typically a different perspective than the frame of the memoir itself). Through this complex interleaving of poems into the narrative, Randall offers a glimpse of the past as remembered from the present, cut through with the past as remembered from a different past, blending together into a complex weave of memory and self-reflection. The first half of each chapter generally traces the chronology of that span in Randall’s life, before the second half collects a less chronological series of anecdotes and remembrances. These recollections tend to revolve around a person with whom Randall shared an important experience or a deeply felt connection. It’s the web of relations that Randall presents in these looser recollections that often gives the work its emotional grace, as when Randall returns to visit a friend in Cuba who presents her with a woolen shawl that Randall had loaned her decades earlier during a chilly nighttime walk. This force of friendship and connection drives both I Never Left Home and Randall’s entire life and work as a writer and activist. These connections are the reason, for example, that El Corno Emplumado is so important to the history of mid-twentieth-century poetry, a fact confirmed by the numerous letters from friends and collaborators with which Randall closes the chapter on her time in Mexico.

Randall inhabits a contradictory space between dominant and emergent cultures throughout I Never Left Home, as her life and work frequently placed her at the cutting edges of the twentieth-century, breaking boundaries with one hand while unconsciously maintaining them with the other. These contradictions are evident in such moments as when Randall decided to move to Mexico as a single mother in 1961—a radical undertaking in either Mexico or the United States at the time—before entering a relatively heteronormative marriage with Sergio Mondragón, co-editor of El corno emplumado. Her marriage to Mondragón was one of several long-term relationships with men before Randall became aware of her queerness when a friend casually assumed her lesbian identity. Randall writes that “Looking back, I believe that the demands of unequal revolutionary struggle were what prevented me from questioning my sexual identity.” One of the sharpest points of Randall’s critique is aimed at leftist revolutionary movements that fail to account for their regressive gender politics. The backward glance with a deeper self-knowledge and understanding of the world characterizes much of I Never Left Home, as does the unconscious compromise between a determined political stance and an inchoate political formation. Randall’s candid narration of the limits of her own understanding in such moments pose as a potent reminder of our own blind spots, of the necessity of constant critical self-examination and willingness to change with the times. Yet Randall’s focus on the tension between the dominant and emergent also points to the fact that the limits on our lives are predetermined if not permanent, as much a matter of possessing an adequate language for critique as the courage to take a stand.

At times, the writing resembles an apology, with Randall remorseful for having failed to escape the prejudices of her time or being unable to anticipate the critiques our contemporary moment has poses—an impossible bar that she sets for herself, yet one that demonstrates her deep and on-going commitment to rooting out all forms of intolerance, inequality, and violence wherever they occur. As Randall’s comments in the introductory first chapter suggest, this apologetic tone at least partially results from the historical events that unfolded during the period of the memoir’s composition, namely the rise of the #MeToo movement and Brett Kavanaugh’s contentious confirmation as a Supreme Court justice in 2018. Randall’s acknowledgement that “I came up in world in which #MeToo was unimaginable” is complemented by an awareness of the on-going barriers to women’s rights in the contemporary world. Randall repeatedly emphasizes both the vast distances that feminist activism has dragged an often-unwilling world, while simultaneously lamenting the frustrating recurrence of the basic structures of power inequalities that mark the history of her life at every scale from the intimate to the global. That fractal structure of power—where violence at a micro level repeats the structures of violence at the macro level—is one of the key ideas Randall reinforces throughout her memoir, comparing her traumatic responses to the sexual abuse she endured in her infancy to the lasting effects of U.S.-sponsored coups and clandestine interventions in Latin America: “the effects of trauma are the same, whether we are looking at an individual or a nation.”

I Never Left Home complements other similar memoirs by women poets, including Diane di Prima’s Recollections of My Life as a Woman (2001) and Carolyn Forché’s What You Have Heard Is True (2019). Thematically, Randall’s work bridges the gap between these other two texts, both highlighting the barriers that women writers faced in the middle decades of the twentieth century, while narrating the joys and traumas of political organizing in Latin America in the face of state terrorism and imperialist violence. If I Never Left Home lacks some of the narrative force of Forché’s memoir, which derives much its momentum from a narrative structure that resembles a detective novel as much as a memoir, it’s because Randall so highly values the communal and the collective, which requires a non-linear and non-hierarchical mode of writing in order to capture the interconnected and decentralized nature of collective social life, rather than relying on the unifying force of an individual’s subjective perspective. Randall’s ability to connect people and her prolific output as a writer have been her chief gifts, both in the sense of the in-grained qualities that define her character and insofar as these represent her primary contributions to the world. Randall gracefully joins these two gifts in I Never Left Home, a rich text that significantly adds to our understanding of life during some of the most important cultural moments and political events of the twentieth century.

Zane Koss is a Canadian poet, translator, and scholar living in Brooklyn, NY. His writing and translations can be found in Asymptote, the Chicago Review, tripwire, the /temz/ Review, and elsewhere. He has published several chapbooks of poetry, including The Odes (incomplete) (above/ground press, 2020), site specificity (Simulacrum Press, 2020), and job site (The Blasted Tree, 2018). Zane is a doctoral candidate in the English Department at New York University, where he researches Canadian, Mexican and U.S. poetry in the 1960s and 1970s.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig