by Angela Moran

Published by Continuum, 2010 | 272 pages

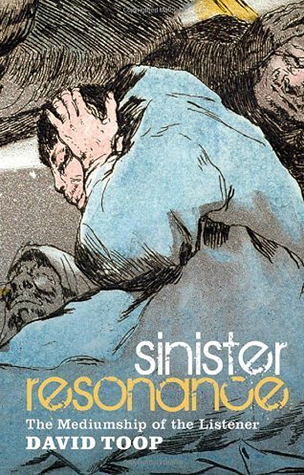

Do we live in an aural age? Few can be better qualified to tell us than David Toop, curator of Sonic Boom, Britain’s first exhibition of architecture and sound, author of Rap Attack, a pioneering work of hip hop scholarship, and resident theorist and historian of modern and contemporary music at The Wire magazine. Sinister Resonance, an expansion of Marcel Duchamp’s reflection that “one can look at seeing but one can’t hear hearing”, interprets the ethereality of sound as it exists in our heads, at its source, all around and in the imagination, and, in so doing, updates our perspectives on sound art experimentation and the philosophies of listening.

Recognizing that “music studies” are numerous, Toop differentiates his own project as a study of “audio culture”, a field he refers to as a “diminutive interloper” in the discourse. This is to say that Sinister Resonance engages with a field of scholarship infrequently responded to in musicology: critical theory. Consider, for instance, Toop’s utilisation of phenomenology in his explication of sound’s “ungraspable” audibility. For Toop, sound lives as either a future or as a past. Known and unknown, it becomes and recedes, moves as apparition into private and public spaces, uninvited, without scent or shape. Created and gone before heard, sound never quite disappears, but thins into a state of extreme materiality. This phantom existence has, for Toop, an ominous, ghostly, sinister quality, evinced immediately to his reader by the titles of the five sections of Part I: “Drowned by voices”, “Each echoing opening; each muffled closure”, “Dark senses”, “Writhing sigla” and “The jagged dog”.

Toop takes his overarching title from Henry Cowell’s Sinister Resonance (1930), a piece for prepared piano, in which the steel strings are adjusted by tapes, putties and chalks and plucked, instead of hammered from the keyboard. Toop’s rendering takes a similar form of bricolage. For starters, Sinister Resonance is not about ours or any specific age, but contains varied cultural expressions that span different times and places: it is filled with historical references, from the fact that preserving spoken voices was Thomas Edison’s original motivation for inventing recording equipment, to the contemporary flash mob event (for Toop a silent-disco situation in which the social power of music is viewed instead of heard).

Neither is Toop’s analysis limited to the auditory. His methodology may undermine a visuocentric world, but he scarcely relegates visual culture in the process. In fact, Sinister Resonance supplements its aural focus with references to a wealth of visual artwork – poems, sculptures, paintings and novels – that, he suggests, can be heard as much as seen. Such a bombardment of examples asserts the fact that our reception of the world is only ever enhanced when ears and eyes combine. Consider Toop’s recognition that eyes and ears have been gendered – in many languages and cultures – as masculine and feminine, respectively (since seeing penetrates and hearing receives). This relates to the musicologist Lucy Green’s argument that, in all performance, women are primarily appreciated for their visual “bodily display”. With this pairing, women become the ears that are seen; the flipside to Toop’s numerous examples of visual art that is heard. In this sense, Sinister Resonance joins a growing corpus of scholarship – including that by Harry White (Music and the Irish Literary Imagination) and Deborah Weagel (Words and Music) – which highlights the active space between looking and listening.

The form of Sinister Resonance closely illustrates the trajectory of sound dispersal. The book’s opening epigram, “For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror” (the ominous declaration of poet Rainer Maria Rilke), becomes a funnel from which many visual case studies spread, like sound particles knocking into each other. That no one example is left to develop as a single linear thought for any length of time provides width rather than depth to the argument. As the Argentinian-born Israeli clarinettist, Giora Fiedman, has explained, “Music doesn’t have borders”. Toop removes borders from all hearing experiences, with a fragmented, transient and unpredictable narrative that itself mimics the act of listening with words.

Unafraid of utilising his own humanity to make the point, Toop locates himself in the study, basing much of his thinking on personal anecdotes, with accounts to the audience – “as I am writing this” – that make for an engaging, almost epistolary delivery. Toop’s use of the present tense in these stories creates the effect of immediacy; the instant impact of hearing on which he expounds is mirrored in his own apparently-spontaneous writing. A cacophony of visual sounds is especially evident in the second part of the book, “Vessels and Volumes”. This whistle stop tour from Joseph Turner to Jodi Hauptman sustains the effect of seeing and listening. We cannot control the high speed in reading such a frenzied montage of artwork, just like we cannot control what we hear, since ears, unlike eyes, do not have lids that close.

Sight verifies our place in one part of the world. Sound does something altogether different. It collapses distance and confuses physical space. This less certain audio-visual world is built for us by David Toop. Reading Sinister Resonance, we come to understand the central nucleus fuelling our fears to be the overriding fact that we die and sound does not. Since the immortal tick-tock of audible time finds its biological equivalent in the fated human heart, all resonance is inherently sinister, ghostly and beyond our existence.

Angela Moran has recently completed a PhD in Music at the University of Cambridge. Her thesis is an urban ethnomusicological study concerned with the development of Irish music by diasporic communities. Angela’s other research interests include popular music studies, film-music theory and gendered musicology. She is also a competent performer on piano, viola and fiddle.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig