Published by MCD, 2020 | 288 pages pages

If you had happened to read Anna Wiener’s Uncanny Valley in January 2020, when this insider’s account of working in Silicon Valley’s “surveillance economy” was first published, the experience must have felt a little like reading George Orwell’s 1984. Like Orwell, Wiener warns of the potential dangers of a world where surveillance and techno-futurist ideologies have run rampantly amok, dramatically threatening human freedom. Only Wiener doesn’t place her dystopia in a hypothetical future, but rather describes a real-world region gone utterly strange: the San Francisco Bay Area of the past decade or so. For anyone reading the book since the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, which began but a few weeks after the memoir’s release, the experience of Wiener’s book—with its depictions of the tech industry’s growing consciousness of its political power, as well as its aspirations for a frictionless, remote-working world for an emerging techno-utopian class—will seem, well, nothing short of uncanny.

Like John Carreyrou’s Bad Blood, which records the wild ambition and systematic deceptions of the defunct biotech unicorn Theranos and its founder Elizabeth Holmes, Uncanny Valley today reads less like a memoir of a dystopian parallel universe and much more like a retrospective documentary of how we got here. Or, rather, it reads like a prophetic warning, as though Wiener somehow intuited that her audience would soon be grounded en masse by the virus and its response, with much time to reflect on the tech industry’s looming capacity as disaster capitalists, busily preparing to take advantage of just such a crisis to further remake the world in its image. Seeking human connection in booming 2010s San Francisco, Wiener’s antennae picked up the static of an emerging techno-capitalist hell, where engineering expediency, and the attendant greed facilitating it, lie coiled to completely remake the social and perhaps the geopolitical order once again.

A native New Yorker, Wiener attended Wesleyan where she studied sociology. After working in the traditional publishing industry in New York after college, she joined an e-book startup, where she had her first encounter with the culture of super-charged tech. From there, she made her way to San Francisco, where she first worked in customer support for the “analytics startup” Mixpanel, and later at the open-source coding repository GitHub. In Uncanny Valley, Wiener tracks her experience as a skeptical but willing flaneur in techie San Francisco. Wiener left tech in 2018, to write this book.

Much of the power of Wiener’s book lies in the innovative mode of its telling, which is highly original. Not only does Wiener change the names of the people with and for whom she worked during her time in San Francisco’s tech community, she renders nearly every proper noun in the book in the abstract. Some of these renderings are obvious: Twitter is ubiquitously referred to as “the microblogging platform.” GitHub, the second company Wiener worked for in San Francisco, becomes the “open-source startup” with the “octopus-cat” logo. Some of her euphemisms are hilarious. Slavov Zizek becomes “a Slovenian philosopher responsible for reintroducing Marxism to a certain subset of my generation—mostly men whose living rooms held extensive vinyl collections and proud little libraries.” There is also a wonderful jab at the local fondness for ultra-expensive retreat centers, like Esalen, which dot the California coast: Wiener calls them “cliffside silent-meditation plantations,” from which people return “inarticulate and asocial.” Altogether subverting the genre of the MFA memoir, the book is highly innovative: it may be the first memoir á clef (i.e. a memoir with a key), as well as a brilliant satire. Think of it as Gulliver’s Travels in Silicon Valley. This key is out there, too: at least one of Wiener’s fans has taken up the project of generating a reverse glossary to assist curious readers with all of Wiener’s references, many of which are expertly skewered.

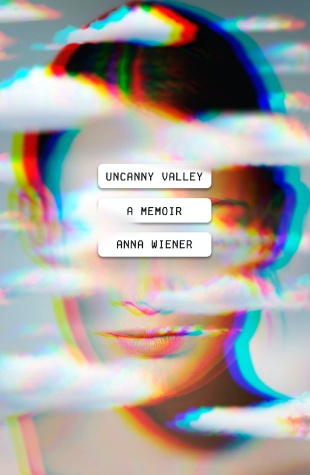

Some readers may be put off by Wiener’s seeming coyness. Yet this storytelling technique is hardly a gimmick, nor just a vehicle for payback. It’s perfectly calibrated to reflect the practices of the industry she describes, where language itself often becomes hollowed, and made to embrace the absurd. This is a phenomenon Wiener reflects upon in considerable depth: “None of the startups in the ecosystem were named for posterity, and certainly not for history,” but by “URL availability.” The title for Wiener’s own memoir functions in quite the same way. The “uncanny valley” has itself by now become a buzz-phrase, so much so that it’s rather amazing Wiener was able to secure the title. Originally a problem in robot design observed in the 1970s by the Japanese robotics researcher Masajiro Mori, the uncanny valley theory posits that as humanoid robot design becomes increasingly more human in appearance and performance, real humans interacting with it tend to become more and more comfortable until the trend flips, becoming an inverted bell-curve where the robot or AI or other humanoid representation becomes not too dissimilar from humans, but also not quite similar enough. In this aesthetic “valley,” the observer or user becomes repulsed, like encountering an animated corpse (Google images of “uncanny valley” at your peril). Although neither the phrase nor the word uncanny occur in Wiener’s memoir, aside from in the title, the implication is that the geographical “uncanny valley” to which it refers—Silicon Valley—has become a place where every signifier of the human threatens to slip from your grasp, if not to shape-shift into the grotesque.

Compared to other representations of the tech epicenter and its influence, such as the hilarious HBO series Silicon Valley, Uncanny Valley comes off as rather dark. The book is laced with a deadpan wit, which makes it a delight to read, but the larger argument and critical vision it presents is far more proximate to Bad Blood. And like the Theranos debacle, the dysfunction it documents has many layers, not least of which is the status of women in the male-dominated engineering culture of the tech world, including the role of entrenched misogyny. Strategically, Wiener never uses the pejorative term “tech bro” to describe the men surrounding her, but they are everywhere. Wiener’s reflections on her own capacity to internalize and perhaps enable their workplace culture make up a significant component of the book’s critique: “I had been seduced by the confidence of young men. They made it look so simple, knowing what you wanted and getting it...I had trusted them to tell me who I was, what mattered, how to live.”

Some of the book’s most disturbing moments document the perverse blindness of San Francisco’s elite to their whiteness and class privilege, especially as it structures their supposed techno-idealism. In one scene, Wiener finds herself arguing with an acquaintance about whether or not nineteenth-century abolitionists in the US represented a positive example of the power of “libertarian contrarianism”—a popular ideological orientation in the world of tech entrepreneurship—to promote “fringe” causes. When Wiener expresses that surely abolition was not a fringe cause when one considers the perspective of millions of slaves, her interlocutor responds, “Okay…But, for the sake of argument, what if we limit our sample to white people?” This line ends a chapter, and the effect is a searing indictment. One imagines the very same interlocutor today in “quarantine” sipping hot cocoa at a posh Tahoe Airbnb, working remotely and pocketing a formidable salary while sharing Instagram slides about BLM and the plight of essential workers.

In the end, Wiener’s direst warnings apply to the dangers of emerging technologies and platforms as instruments of surveillance. These growing threats, in her view, are underrecognized among tech workers and entrepreneurs alike. In the memoir, when news breaks of an “NSA whistleblower”—undoubtedly Edward Snowden, who in 2013 revealed widespread spying by the NSA on American citizens through collaborations with major tech companies—Wiener notes that her friends are conspicuously silent about their own implication in the development of surveillance infrastructure. She finds herself increasingly disturbed by how much data she and her colleagues have access to, and how it might be exploited or abused. She writes about how she would “wonder whether the NSA whistleblower had been the first moral test for my generation of entrepreneurs and tech workers, and we had blown it.” As Wiener notes, tech companies already call their customers “users,” like a drug cartel. Indeed, for Wiener tech has become thoroughly imbricated in the malevolent structures of what Shoshana Zuboff has called “surveillance capitalism,” and its power is expanding exponentially. Perhaps the most cogent expression of this transpires in the book’s epilogue, which takes place shortly after the 2016 election, where Wiener reflects on the dismay her colleagues felt upon the election of Donald Trump to the presidency, including the increasing appearance within their own systems of white nationalist and other dangerous propaganda. Somberly discussing the situation with another colleague from her tech milieu, Wiener recalls how the conversation turned unexpectedly from the newly elected government back to tech itself: “‘There are no adults in the White House,’ he said, with a trace of a smile. ‘We’re the government now.’”

Regardless of your politics, that’s an unsettling statement. One might be inclined to read this technocrat’s “trace of a smile” as vanity, if not a whiff of hubris, especially given the scale of techno-utopian ambition depicted elsewhere in this book. From an acquaintance who wants to build a “blank-slate city” in a place like El Salvador (is El Salvador a blank slate?) to schemes of “biohacking” and Theranos-ian biometric surveillance that would border on quasi-eugenicist if they didn’t seem so useless (“just metadata,” Wiener asserts), the tech world of Uncanny Valley is a veritable catalogue of schemes aspiring to disrupt institutions and remake the world. To what end? Wiener seems to want us to wonder. And we should: even though some of the more far-fetched phenomena she describes may have seemed like speculation and niche-trends in the world of Uncanny Valley, in the short time since the book’s publication, versions of both of them have entered mainstream reality. It’s uncanny. To say the least. Like trying to make eye contact during a Zoom call.

Kevin C. Moore teaches in the Program in Writing and Rhetoric at Stanford University. He earned his PhD in English from UCLA in 2013, and taught at UC Santa Barbara from 2013-2019. His research interests include propaganda studies, science and rhetoric, trust, writer’s block, and Ralph Ellison. His work has appeared in Arts, Arizona Quarterly, Composition Studies, Writing on the Edge, MAKE, and Souciant, as well as a number of edited collections. He also writes fiction and creative nonfiction. He lives in San Francisco.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig