by Katherine Preston

Published by The University of Michigan Press, 2013 | 279 pages

After enjoying a cultural and economic flowering between World War II and the Civil Rights Movement, Detroit has crumbled, so the story goes, into dilapidation and decay. The most prominent features of this collapse are what Detroit commentators have called the “deindustrialization, ghettoization, and racialized poverty” that have increasingly marked the city since the 1950s. What has too often gone unremarked, however, are the ways in which one of Detroit’s most disenfranchised groups – the Black LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender) population – has responded with innovation and artistry to such segregation, poverty, and other social conditions that construct Black LGBT lives as inconsequential. Butch Queens Up in Pumps, Bailey’s enthnography of Black LGBT ballroom culture, explores this often controversial and hugely influential performance practice, competitive culture, and kinship community that affirms expressions of non-normative gender and sexuality and enhances the lives of Black LGBT people in the largest – and one of the poorest – American cities with a majority Black population.

Marginalized racially, sexually, and economically, many of Detroit’s Black LGBT people are denied access to multiple spheres, from their religiously regulated and patriarchal “Black communities of origin,” to White queer spaces, economic opportunities, and effective healthcare. Bailey’s text details the ways in which Ballroom culture, through prizing the expression of fluid gender and sexuality, actively forming kinship structures, and ritualizing performance and competition, institutes a space of care, love, competition, labor, critique, worth, and belonging for Black LGBT individuals. Detroit Ballroom culture, Bailey shows, manifests the agency of Black LGBT people to “build and maintain a community in the midst of crisis” and to actively “alter the discursive rendering of Black LGBT people as worthless.”

While other studies, most famously Jennie Livingston’s documentary film Paris is Burning (1990), have introduced Ballroom to mainstream audiences, they have often focused only on Ballroom in major urban centers like New York City and therefore “provide only a glimpse into this cultural practice.” Butch Queens outlines Ballroom culture as a whole, but it also specifies its relevance and particularities in Detroit. Like Livingston, Bailey observes Ballroom and reports his findings on Black queer formation. But as a Black gay man, Bailey participates in the Ballroom community in ways that Livingston, as a white woman, cannot. He draws out Ballroom’s intricacies through a method called “coperformative witnessing.” Unlike observing and reporting, coperformative witnessing “requires one to perform and lend one’s own body and labor to the process involved in the cultural formation under study, particularly when it involves a struggle for social justice.” Bailey, who serves on the board of directors for The House of Blahnik, started this book project as a member of The Legendary House of Prestige, even winning the competitive category of Executive Realness for his house at the Love is the Message Ball in 2005. He presently serves as a Ballroom community leader and advocate for HIV/AIDS prevention.

Ballroom began in Harlem in the 1920s, and continues to change and evolve. It has spread to metropolises such as Atlanta, Washington DC, and Los Angeles, and to smaller cities such as Cleveland, Buffalo, and Pittsburgh, to Afro-Canadian communities in Toronto, and even to Japan. Despite regional differences, ballroom culture is organized into houses, which are “family-like structures that are configured socially rather than biologically.” Each house has a unifying name, most of which are inspired by haute couture designers, such as The House of Givenchy or The House of Ford; other houses take on names specifying qualities that the house leaders, called Mothers and Fathers, value, such as The House of Prestige or The House of Prodigy. The house Mothers and Fathers, called house parents, are experienced and successful leaders or performers in the Ballroom community. They mentor other members of the house, called children or kids, who are less experienced in Ballroom and may or may not be younger than their house parents. Houses are not “actual buildings,” Bailey emphasizes. They instead name the ways in which members “interact with each other as a family unit,” which includes encountering conflict, providing emotional and economic support, attention, mentorship, critique, competition, and experiencing break-up, reconciliation, and care. These houses provide alternative relationship structures not only within mainstream heteropatriarchal culture, but also within mainstream queer culture, as they represent family free from what some consider disciplining institutions such as marriage, gay or otherwise.

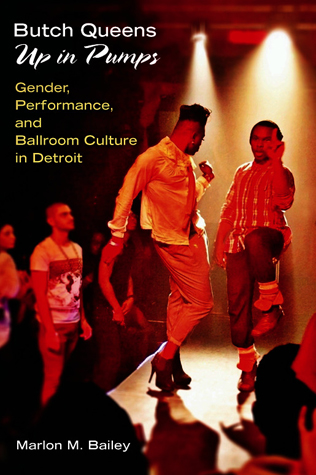

The “most conspicuous function of houses,” Bailey notes, “is organizing and competing in ball events.” Balls are lavish competitive events hosted by houses. House members compete as a team in categories against members of other houses to “snatch” trophies, win monetary prizes, earn prestige from the Ballroom community, express creativity, and experience Black belonging. Ball events are manifestations of what Bailey calls “Black queer space,” in which expressions of gender, sexuality, performance, and community of the kinds valued and experienced in Black spheres can be expressed, contested, and reworked. What Bailey names the gender system undergirds balls’ competitive categories and represents the “complicated and multidimensional” gendered and sexual subjectivities Ballroom members perform at balls and self-fashion in their daily lives. Although there are a broad range of gender and sexual subjectivities, some of the most prevalent are Butch Queens (gay or bisexual male-bodied men), Femme Queens (transgender women or MTF [male to female] women), Butches (transgender men or FTM [female to male] men), Women (female-bodied women), and Men (male-bodied men who do not identify as gay).

Butch Queens, Femme Queens, and others compete in categories spanning an interlocked range of gendered, raced, and sexualized subjectivities which include Thug Realness (performing thug masculinity), Executive Realness (performing white-collar professionalism), Body (showcasing body parts and accoutrements that help members to pass, for example, as “real” in the public sphere), Sex Siren (showcasing virile masculinity such as penis size and musculature), and Realness with a Twist (performing the ability to switch quickly between expressions of masculinity and femininity). Scholars have argued that associating the performance with the moniker of “realness” reifies rather than unsettles normative gender and sexuality. Bailey concedes that Ballroom is not utopic: the scene privileges males and masculinity (there are more categories for Butch Queens than for any other gender or sexual expression). But striving for realness, in Bailey’s account, does not simply “reinscribe the same norms that it purports to subvert.” “Notwithstanding the substantial prominence in the Ballroom scene that Butch Queens enjoy,” Bailey argues that “insufficient attention has been paid to them as a transgressive category of gender” who “reflect a collapse of the masculine/feminine binary of gender presentation and performance.” The labor necessary to perform realness in fact “reflects possibilities of reconstituting gender and sexual subjectivities.” Ballroom presents gender and sexuality as both effects of invention and as invitations to invent other subjectivities. As Ballroom spreads both regionally and globally and underrepresented voices, such as those of women and adolescents, become more prominent in the scene, members seek “innovative ways to include new kinds of gender and sexual subjectivities” to “counter the increasingly perilous conditions under which Black LGBT live.” Additionally, striving for realness is for Bailey not so much reifying gender and sexual categories as it is a strategy to increase the likelihood that Ballroom members, vulnerable to physical and emotional violence for their non-normative gendered and sexed expressions, will “avoid homophobic discrimination, exclusion, . . . and death” in a “transphobic and femmephobic public sphere.”

I do wish that Bailey, in his investigation of realness, would have explored more thoroughly the possibility that Ballroom members are not the only ones self-consciously performing realness. Bailey opens up but does not explore the idea that thug or executive realness, for instance, as it is performed by Black men regardless of sexual affiliation in everyday Detroit, might equally be a performance of availability for queer sexual encounters as for straight ones. And despite the problematic unacknowledged appropriation of Ballroom feminine realness by White women entertainers such as Britney Spears and Lady Gaga, I also would have liked to have seen Bailey explore further the ways in which performing feminine realness has surprisingly undergirded gender and sexual expression – not to mention pleasure and joy – for innumerable people outside the Ballroom community. And finally, Bailey’s devotion to the specificity of Detroit Ballroom culture compelled me to wonder what kinds of regional dance or performance patterns, trends, or inventions he sees as specific to Detroit members, distinguishing their art from that of members in other large urban centers, such as New York City or Atlanta.

Bailey’s study culminates in his chapter “‘They Want Us Sick’: Ballroom Culture and the Politics of HIV/AIDS.” Here Bailey offers one of his most moving and revolutionary stances. In its affirmation of fluid and various sexual practices, Ballroom is not only situated to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS, but already does so in ways that have gone unremarked by HIV/AIDS prevention specialists. Counter to mainstream prevention programs, Bailey argues that it is not the virus that kills people, but the stigma associated with it that prevents people – including HIV/AIDS experts and counselors who often hold heterosexist ideologies – from openly addressing practices that increase risk of contracting HIV and the ways to reduce risk. In fact, multiple exclusions from access to open communication, healthcare, and kinship have contributed to the rise of HIV contraction in the Black LGBT community. Such exclusion has produced feelings of self-worthlessness, which subsequently contributes to members believing that their lives are expendable and not worth the labor of health and wellness. Ballroom, through its relentless labor of constructing Black belonging and valuation of Black LBGT lives and aspirations, counters what Bailey calls “the social conditions” that produce psychic and structural “risk factors” for Black LGBT individuals.

For these reasons, mainstream HIV/AIDS intervention prevention strategies have much to learn from Ballroom’s intravention strategies. Whereas intervention names two disparate communities (the binary of professional experts and non-experts), intravention assumes coproducers of knowledge and expertise. Ballroom practices HIV intravention on multiple registers: affirming both non-normative sexual behaviors and the people who practice them; house parents who inform, educate, and care for their house children’s wellbeing regardless of their seroconversion status; and the organization of prevention balls whose purposes are to increase education about sexual practices and to value the lives of those who have already contracted HIV.

Butch Queens Up in Pumps is essential reading for those interested in gender and sexuality. Bailey’s work shows that there is not merely the (as in a singular) white-washed history of sexuality characterized by subjection, as Michel Foucault might have it; sexuality’s history is multiple, heterogeneous, and saturated with Black queer agency. Butch Queens Up in Pumps points to many futures of sexuality, as Ballroom continues to grow, transform, and invent sexual subjectivities and communities of creativity and care for countless individuals.

Ben Bagocius is completing his PhD in English literature at Indiana University-Bloomington, and his dissertation examines the ways in which fin-de-siècle science offers vocabularies for literary artists to unsettle axioms of and reinvent the sexual. He received a B.A. in English from Kenyon College in Ohio, an M.F.A. in creative writing from New School University in New York City, and is book review editor of Victorian Studies. Ben is also the 2006 and 2010 U.S. Figure Skating adult Midwestern champion.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig