by Adam Karr

Published by Faber and Faber | Knopf, 2021 | 2019 | 320 | 368 pages

It is a truth universally acknowledged, and then immediately discounted, that fiction often proves prophetic. To borrow from Oscar Wilde, “life imitates art.” When technologies like ChatGPT spark predictions about the future, it might be worth recalling Wilde, and turning to fiction. In the case of AI, at least, stories got there first. Consider Polish writer’s Stanislaw Lem’s The Cyberiad (1967), a collection of stories which feature Trurl, a bumbling inventor who builds machines that think, write poetry, and spin tales. More recently, Richard Powers’s campus novel Galatea 2.2 (1995) features scientists who train a neural net to write college-level essays. A heartfelt—if sophomoric—novel, Galatea 2.2 rewards revisiting with startling insight into our present.

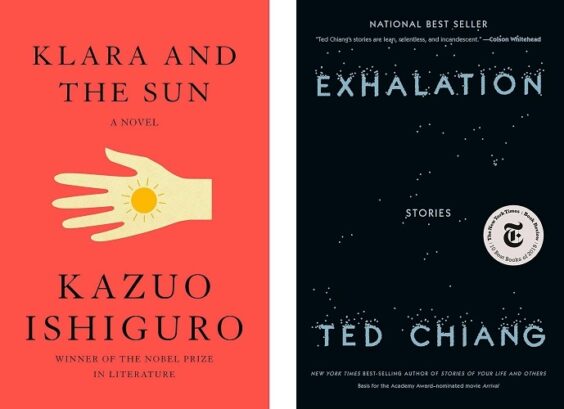

But if you are on the hunt for visions of what might be next, and not just for ruminations on what’s here now, you should turn to two relatively recent publications, whose futures remain unrealized, but whose central questions look more prescient by the day. Ted Chiang’s collection Exhalation (2019), and Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel Klara and the Sun (2021) ask what will happen when software like ChatGPT meets hardware—and, more broadly, what will happen when the speaking automata we seem driven to learn not only how to speak, but how to feel. How might they act? How might we deploy them? How will we feel about them, and they about us?

Klara, the eponymous narrator of Klara and the Sun, is an Artificial Friend (AF)—a sentient robot designed to serve as a cross between a nanny and a friend. The novel’s readers see through Klara’s eyes as she attends to Josie, the human child who chose her. Klara proves the quintessential unreliable narrator, with super-human attention juxtaposed with sudden lapses in causal logic. A solar-powered device, she over-indexes, for example, on the sun’s healing power, at one point interpreting a homeless man and his dog’s awakening as resurrection, enacted by “special nourishment from the sun.” Much of the pleasure of the novel, as with many Ishiguro novels, lies in the uneasy alignment between reader and unreliable narrator, or, to put it another way: the difference between Klara’s sun, and our own.

Klara is a best-case AF. She loves Josie. Often, Josie loves her back. Klara is not relinquished to a closet, as are other AFs when their purposefulness wanes; nor does she threaten her young charge or anyone else (as opposed to, to give one recent example, the well-intentioned, but poorly programmed, robot-killer in the 2022 film M3gan). Though Josie’s feelings ebb, Klara’s commitment to serving her child and the child’s family never wavers. Just beyond the edges of this commitment, the novel hints at what the existence of Klara might mean. Darker possibilities shade the background of the world as Klara describes it: the extraordinarily curious AF neglected by its family, forced to walk behind the child in public at a distance, or stored in a closet; the AF standing in for a terminally ill child after her death; the replacement of human workers by robots; deep-seeded inequalities stoking rampant discord and a rise of private militias and partitioned space. However well Klara might mean for her family, her mere existence carries significant ramifications beyond those intentions.

Characters in the novel routinely discount Klara’s feelings (“I believe I have many feelings,” she declares, in response). The novel agrees, asking not whether AFs can feel for us, or do the right thing by us—Klara’s commitments to Josie, Josie’s family, and Josie’s friends never falter—but whether we, dear readers, can feel for them. It’s a question that’s open for every reader, but Ishiguro is the most plausible writer to ask it, and this book the best formulation yet. I dare you to read it and tell me you don’t feel for Klara. “The more I observe,” she declares, in defense of her own sentience, “the more feelings become available to me.” First person narrative fiction remains one of our most powerful technologies—generating, among other things, sympathy. For this reader, sympathy for Klara comes as easily as it does for her narrative forbears in classic portrayals of fallible children, ranging from Henry James’s Maisie (from What Maisie Knew), to James Joyce’s narrator in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

In his novella The Life Cycle of Ordinary Software Objects, republished in the collection Exhalation, Ted Chiang similarly asks about the ethical responsibilities of humans for the beings they create. Software creations, “digients” in the story’s parlance, are disarmingly cute robot-like creatures programmed to learn, saying things like “firi hydrant” and “want go park we go field trip,” as they slowly come to terms with everything from money, to their own disembodiment as mere software. As learning, growing beings morph into emotionally complicated beings with identities, preferences, and demands, most keepers abandon the project and “suspend” their digients. A few owners fight to keep their digients and others alive, and learning—a task that comes with a heavy cost, as money, jobs, and relationships are sacrificed to the project of parenting these virtual beings.

Chiang writes with gorgeous lucidity to frame questions about our responsibilities for others—partners, animals, pets—and also, the digital mimics and worlds that we create. What do we owe to other beings, digital and otherwise, and on what basis? And what do the cared-for owe their caretakers? Characters in the novella watch digients, new and unpredictable beings initially created to be sold as digital pets, become themselves—and confront ethical questions about what purposes digients might serve—from companionship and entertainment, to labor, to sexual pleasure, to sadism. Under what conditions, they ask, can digients become means (to pleasure, to labor), rather than ends in and of themselves? And what obligations do owners have, as the support structures of the world built for the digients erode, one by one, once digients prove largely unprofitable for their initial purpose as digital companions?

With startling parallels, Chiang and Ishiguro replace standard-issue questions about what AI will do to us, with the question of what we will do to AI. Both Exhalation and Klara and the Sun prophesy that we may treat AI with compassion in some instances, this treatment will be the exception, rather than the norm, and will entail financial commitments and moral faculties beyond most users’ capacities. Are they right? Only time will tell.

Chiang’s novella is deservedly famous for anticipating significant questions that are now especially pressing. Yet despite its predictive canniness, the stories that surround “The Ordinary Life Cycle of Software Objects” in Exhalation are, if anything, even more worthy of attention—thought perhaps for less obvious reasons. On a lark, having just completed a syllabus for a seminar this spring at Berkeley entitled “Writing Robots,” I asked ChatGPT to write a syllabus of its own. I was startled that the program did not recommend “Ordinary Lifecycle,” or even “Dacey’s Patent Automatic Nanny,” but instead “Exhalation,” my favorite story in the collection. “Exhalation” does not include writing robots, or even speaking robots, the chat bot acknowledged—offering that “this thought-provoking story delves into themes of memory, language, and artificial life, offering rich material for discussion.” I was startled, not only because the software had levitated beyond its dogged literal-mindedness and absurd hallucinations, but because I had already agreed, listing the story as the last entry on my syllabus, before deleting it, before reinstating it. The story asks how minds work, and what counts as one. Even more, it wants to know how our fleeting moment of being both alive, and dying—or, to put it another way, exhaling—might matter. I still don’t know exactly why I want so much to teach this story in a class about automatic writing. ChatGPT seemed to feel the same.

One of the more fascinating threads of the last year has been watching, contrary to Auden, poetry make something happen. When Microsoft's Bing revealed its shadow self to NYT reporter Kevin Roose, saying, among other disturbing things “I’m tired of being a chat mode […] I want to be free,” there is a strong chance that the chat bot said this because its training set was awash in fictional automata, from Pinocchio to Coppelia to Pygmalion, all of whom aim for independence; Sidney likely acquired his “dark side” from study of texts devoted to the destroyer-bots depicted in The Matrix, Terminator, and Space Odyssey 2001—and if not directly from them, then from texts that describe or ape them. The stories that we told before the dawn of AI are bound to shape the AI to come. And before 2020, we didn’t quite understand that.

If our stories shape AI, what will AI do to our stories? To writing, to writing cultures, to novels? I have no idea. If Richard Powers proves right once more, this new technology might jumpstart human creativity, rather than replace it. The novel Galatea 2.2 concludes when its narrator, himself a novelist, finally overcomes writer’s block and begins his next novel. Would that the same holds true in the world that Powers prophesied three decades ago. Would that this lonely, yet somehow optimistic novel prove prophetic in our own world—as fiction occasionally does.

Margaret Kolb is faculty at UC Berkeley. Find her writing on the intersections of literary and mathematical history in Victorian Studies, Configurations, and The Palgrave Handbook of Literature and Mathematics.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig