by by Margaret Kolb

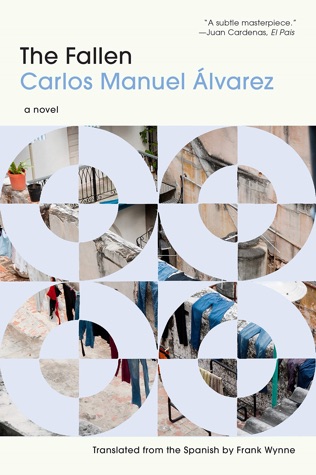

Published by Graywolf Press, 2019 | 143 pages

Translated from the Spanish by Frank Wynne

Cuba has become a loaded subject. The idea of Cuba is so politicized that it feels almost impossible for outsiders to know what life in the country is really like. Muddled discourse around the recent anti-government protests in Cuba reflects this paradigm. The protests of July 2021 also demonstrated the diversity of perspectives within Cuba; protesters registered myriad, sometimes conflicting demands and frustrations. These frustrations included shortages and economic crisis exacerbated by the American embargo and sanctions, restricted civil liberties (particularly of free expression), the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, and inequality exacerbated by the island's dependence on tourism. Of course, it is impossible to know every participant's motive, just as it is impossible to represent Cuba through the perspective of any one individual.

Carlos Manuel Álvarez's The Fallen offers multiple experiences of living in Cuba through the voices of a contemporary Cuban family of four. The 18-year-old younger brother of the family, Diego, speaks first. He is a compulsory soldier serving his time in a military camp, stewing over a general sense of unfairness in his country and a felt lack of attention from his parents. Diego's mother, Mariana, keeps having seizures. She frequently receives phone calls from a mysterious "shrill and mocking" voice that makes homophobic claims about her daughter, among other accusations, and "sometimes cackles and adds: I'm inside your head." Mariana's husband Armando is a devotee of Cuban national ideology who heroicizes the past. With a tightly held sense of morality, he permits no license at the hotel he manages. María, the daughter of the family, suffers deeply from the stress of her mother's condition and her sense of obligations. With her friend René she had been skimming from the hotel where they both worked under Armando, but she has lost his friendship as he believes she betrayed their scheme to her father.

The book's title invokes not only the state of fallenness, both the fall that interrupts one's march forward or the fall from power and grace, but also resonates with death, particularly of soldiers in nationalistic sacrifice. The word fallen also implies a state of suspension—as a curtain falls—or even to have been dropped. A state of suspension is particularly resonant to the novel as the characters feel stuck in the routine of their lives with no clear vision of their own or their country's future. Four sections rotate in the same order—"The Son," then "The Mother," "The Father," and finally "The Daughter"—five times across as many parts. The titles of each section suggest we might read the novel's characters as symbols or representatives of their social, particularly familial, positions. Yet Álvarez's characters also have names and feel like real people, too.

Each character offers a different perspective on and method for coping in contemporary Cuba. Diego's experience in the military is tedious; he feels that "everything we do we do while sleeping." The teenager's coping mechanisms are immature, but his resentment for the ideological and idealistic charade of fairness and equality in Cuba, particularly as embodied by his father, is understandable. Armando is both melancholic and idealistic. His car keeps stalling mysteriously. He fears that he has missed a glorious epoch of communism and is deeply invested in patriarchal lines of inheritance. Leftist heroes populate his dreams and he repeatedly shares a story about Che Guevara refusing the gift of a bicycle for his daughter because it "belonged to the State." A sense of moral superiority and toxic masculinity consoles Armando: "But I am an honest man and I endure, a man who knows that the heroes of our country endured much worse, a man who knows that real men hold their pain inside."

Gender seems to make a difference in the family members' experiences. While the men are more inclined to grand narratives, the women feel especially isolated and trapped. Mariana feels estranged from the world. Her sections often describe memories or hyper-focus on something quotidian as she is mostly confined to her home. She feels guilty for her children's experience of the "special period" of extreme scarcity in the wake of the Soviet Union's collapse, as if she could have done more for them. Comparable to her mother's condition, María seems to live outside herself, though she is well enough to constantly direct her attention toward work and supporting her family. Yet she reflects more than she lets on:

"I wonder about that, although to tell the truth, I wonder about a lot of other things. Where Mamá's illness came from, for example. Whether I enjoy my job. Whether I like having to shoulder the responsibility for everything at home. What my parents were like before they were my parents. But, most of all, the big question, the million-dollar question, the question that has haunted me my whole life, one that sounds preposterous yet somehow isn't: Why do neither of them eat chicken, in any form, and why have they never talked about it?"Still, María's strategy ultimately is repression—"if you don't think about it, you don't notice. But if you do think about it, even for a second, there's always some tiny part of your body that is about to itch or ache."

One other character, René, is portrayed in significant detail. His character, described primarily by María, offers an account of a Cuban from a different region than the main characters (the east). René is of a lower class, to the extent that class exists or is acknowledged in Cuba. María explains: "in eastern Cuba, people are poorer than anywhere else, they have to be, it's practically the law." René has survived a horrific accident working in a heavy metal processing plant. Though The Fallen never mentions race explicitly, it is possible that René is Black, according to the demographics of his region. As the son of a sex worker raised in part by his neighbors, René reminds us of people in positions other than the four main heteropatriarchal options and the depth of precarity in Cuba.

The Fallen is largely concerned with looking—the objects of one's focus and the ability to see at all. Most simply, there is a 'looking the other way' in petty corruption. The book is also interested in being seen by others. Reflecting on the falling out between Mariana and her former friend, co-teacher, and neighbor Migdalia, María notes: "All I know is that, while the time to patch things up came and went, they were looking the other way." The friends slowly stopped talking in the wake of tensions caused by the arrival of a television and phone to be shared by the building but kept in one household, and now Migdalia has become a kind of enemy and scapegoat to Mariana. The perspective of Diego and María as children seems to offer a clarity that adults with their traumas and ideological commitments perhaps lose touch with: "we could see everything that was going on up there, in the adult world." The siblings as children also managed to maintain authentic relationships with each other: "We also had the ability to see each other. We were not yet completely invisible."

The connection between Álvarez's subjects and the objects around them is often broken or distorted; Diego describes feeling "as though the objects, forms, and concepts that make up the world refuse to be observed." While Diego feels perhaps that things are unknowable, Armando suggests things are obscured but can be known. After several beers Armando has an experience where he "no longer saw the static image of my apartment, its walls and furniture, but glimpsed what was hidden within that image." While Armando's uncanny object relations are external to his sense of self, Mariana feels alienated from her own body: "My body is like a country I sometimes visit." Mariana's vision is surreal as she dives deeply into the sea of herself to find "small blind lobsters, delicate, timid creatures, terrified and misshapen in their panic." She sees these and other shapes, but "can't quite make them out." María also has a surreal experience in witnessing her mother's seizure, where her mother's ghostly hands keep scrubbing laundry as the rest of her falls away.

Álvarez's first novel, The Fallen has been translated from Spanish by Frank Wynne. The novel is highly descriptive and written mainly for a non-Cuban audience. The speakers, particularly the son, employ locutions that imply an address to readers: "But I'd like to draw attention to two things," says Diego. "We have a lot of hopes tied up in that boy. We expect him to go a little further than we did," says Armando. Álvarez takes the time to note and describe Cuban basics like the small size of typical coffee cups and parenthetically explain "(In Cuba, it's the Three Wise Men who bring children presents at Christmas.)." However, The Fallen is not a guidebook or a history text. Álvarez remains focused on the present and the particular experiences of one family, though his characters also remember and describe the past. The book also juxtaposes moments of clarity and explanation with moments of metaphor and uncertainty. As the characters often describe each other, sometimes in free indirect discourse that blurs the perspectives of the speaker and the subject, the novel further complicates the truth or reliability of the novel's representations.

The Fallen ultimately conveys a profound ennui. The repetition of its cycle through the family's four voices feels like a cube turning around to each of its sides, but the cube doesn't go anywhere (it does not roll). Álvarez favors geometric metaphors himself, as the son muses that "any segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line" and "at some point, everything intersects." Armando believes "the people were marching toward a bright future, along the perfectly paved road of the future, we had only to keep marching, to move from one point to another." These images help the novel build its sense of inertia and a kind of passivity in the face of inevitability. This passivity also manifests in a trope of sleep and recurring dreams, at least for the two male characters. When Armando's dream finally changes, it has merged with his reality, leaving readers to guess what is real or not. Álvarez leaves us with a state of deferral and self-consumption. There seems to be no way forward from here, but perhaps there is still some chance that Álvarez's characters can awaken to another, perhaps non-linear, existence.

Katherine Preston is an English PhD candidate at Brown University. She holds a B.A. in English and Political Science from Williams College. She specializes in poetry and poetics with a particular interest in black aesthetics.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig