by by Margaret Kolb

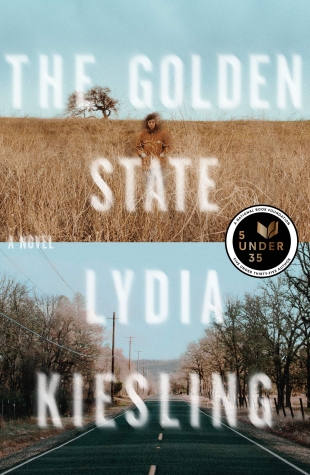

Published by MCD, 2018 | 304 pages

Lydia Kiesling’s debut novel, The Golden State, begins with the titular first line of Philip Larkin’s melancholy poem, “Home is so sad.” Larkin wrote the poem in 1958 while visiting his mother for Christmas, a detail that aptly illuminates the central concerns of Kiesling’s story about mothers, nostalgia, and home.

The Golden State is a road trip novel that, like its archetypal predecessor On the Road, reads as a distinctly American story. The premise of the novel is simple: in the midst of what she later describes as a breakdown, Kiesling’s Daphne leaves early from her job at the Institute for the Study of Islamic Societies and Civilizations, grabs her year and half old daughter, Honey, and drives from San Francisco to Alta Vista, her fictional home town. During her 9 day stay in Alta Vista, Daphne finds herself in the company of two other women: Cindy, an alt-right separatist who lives next door, and Alice, a 92 year old widow on a road trip of her own. As she is unwittingly drawn into a local separatist movement through conversations with Cindy, and through her attempts to help Alice complete the last leg of her own journey, Daphne is forced to reckon with what it means to call “the Golden State” home, and to confront forms of loss and separation previously unknown to her.

Daphne’s breakdown is precipitated by two traumatic events: the now eight-month absence of her husband, Engin, who was coerced into surrendering his Green Card and deported to Turkey due to an administrative error and – Daphne suspects – Islamophobia; and the death of Ellery, a young graduate student who died in a car crash in Turkey while doing research funded by the Institute where Daphne works. Now living as a single mother, Daphne feels like a victim of circumstances that are beyond her control.

The nine chapters of the novel, which represent each day of the nine-day visit to Alta Vista, narrate Daphne’s attempts to grapple with the trauma of these still-unfolding events, as well as the persistent terrors of new motherhood. Is she a fit or unfit mother? What does it mean that she hasn’t been able to quit smoking? Was going back to work, which required her to miss months of crucial early development time with her baby, worth it? Daphne is, of course, a very good mother by any reasonable standard. This is not a story about wayward parenting so much as it is about the ways in which life in the Golden State – with its brutally high cost of living – forces parents to make decisions about work and childcare that can feel mercenary.

The significant difference between Kerouac’s and Kiesling’s novels is that in The Golden State the protagonist is a woman and a mother. Whereas in On the Road, the practical and emotional concerns of women and children are marginalized to make space for the concerns of men in search of increasingly inventive ways to prolong their adolescence – that is, to stay on the road – Daphne cannot afford to have Honey and her needs out of sight or out of mind, even for a minute. Daphne’s wrenching and bottomless love for Honey is beautifully represented through Kiesling’s description of Daphne’s attempts to pass an evening in Alta Vista by watching old videos of 8-month-old Honey on her daycare provider’s website. The tone of this description, much like the tone of the entire novel, is celebratory and mournful. Daphne delights in watching her beautiful, “beatific” baby, but also grieves the loss of this baby who is now a toddler. In the video, Honey is wearing a printed onesie featuring trains, planes and automobiles. Daphne recalls having told Honey that day, “You are going to be a baby who goes places,” and yet she has mostly stayed right where she was born: California. In this way Kiesling establishes how The Golden State can be read as a feminist revisioning of the road trip novel through the persistent presence of Honey, and Daphne’s persistent concern for her. Honey’s dynamism, represented through her rapid physical growth and change, in no way diminishes her need for the stability of a home, which only her mother at this point can provide. As much as Daphne may desire to wander, her sense of responsibility to her daughter drive her to ground herself, to take root in the place she knows best, California.

Though Daphne, who could very well move to Turkey and live with Engin and his family, complains about her $69,500 salary, “which is somehow not enough to live on here but well above the national median household income,” she hesitates to forsake her home for her husband’s. She thinks, “If I leave I am sure we are never coming back, and she’s a California baby now and if we leave she won’t ever be again.” The allure of California may be elusive to many – and recent reports show that more people are leaving the state than ever before – but millions continue to endure its high cost of living, wildfires, and vast inequalities, for a variety of reasons. As Kerouac professed in On the Road, “I wanted to get to San Francisco, everybody wants to get to San Francisco and what for? In God’s name and under stars what for? For joy, for kicks, for something burning in the night.” Daphne’s reasons for staying in San Francisco—her “glass-walled office,” the fact that San Francisco is a “top five American city”—are as vague and quixotic as Kerouac’s, but this does not make them any less compelling, or consequential.

The novel’s title proves to be ironic, as the California of Kiesling’s novel proves to be unlike the prosperous and gold-rich paradise suggested by its nickname. Kiesling represents the residents of Daphne’s hometown, the fictional Alta Vista, as “down-trodden,” crypto-racist, anti-immigrant white separatists who are trying to secede from California and create their own 51st state of Jefferson. Motivated by nostalgia for a time in Northern California that likely never really existed, Daphne describes her neighbors as people who crave “economic independence for what is probably the poorest county in the state and the largest per capita user of social services.” Kiesling positions Daphne’s desire to maintain Honey’s “California baby” status, even if it keeps her separated from Engin, in parallel to the separatists ardent yet misguided fight for the heart and soul of California. Despite their differences, the Californians Kiesling represents are all equally and understandably deluded by the allure of “the golden state.”

Daphne’s and Honey’s interactions with the separatists is broken up by her encounter with Alice, who has also embarked on a road trip across California. Alice desires to visit a camp on the Oregon border where her husband once worked. Like Daphne, Alice has had her husband taken away from her, except the cause here is illness, not immigration status. Alice’s story is undeniably tragic. All three of her children died young, and her husband fell ill shortly after the last child’s death. Interwoven with the separatists’ political drama, Alice’s story reminds us that there are two bodies or institutions under duress here—the Golden State, and motherhood. While Daphne has never experienced a loss like Alice’s, she identifies with Alice’s unfathomable loss as she fantasizes about all of the awful ways in which she could lose Honey—a car accident where her car seat is facing forward, not backwards, glass shattering her throat; strangled to death in the blind cords… She also identifies with Alice’s nostalgia for the past, which can only be satisfied by returning to the place – no matter how much it has changed – that once felt like home.

Despite the realness of her anxiety as a mother who is never sure if her decisions are in the best interest of her husband or child, Daphne always knowingly presents herself as still fortunate, and still capable of redemption. As Kiesling is careful to avoid idealizing Daphne, her expressions of frustration and rage are always counterbalanced by an awareness of her privilege as an educated white woman, and the mother of a living, breathing child. If it was not for her job at the Institute, Engin might not have moved to California to support her career, and he would have never experienced deportation as a “casualty of militarized bureaucracy and nativism.” And yet how grateful she should be that at the end of her maternity leave, she “went back to a beautiful glass office and not to a sweatshop or a goddamn subway sandwich shop or to be a nanny in Westchester County.” Daphne’s unfiltered inner monologues, so often tinged with sarcasm, appear as her only means of coping with the seemingly impossible dilemmas and unlimited opportunities for grief that motherhood presents to women. If Daphne had never encouraged Ellery to do her research in Turkey, she would still be alive, and Ellery’s mother would not have to mourn. And yet, as the experience of motherhood has taught Daphne, “to have a child is to court loss.” We live in a time when steady employment and the safety of one’s children and family are not to be taken for granted. The exuberant joy, humility, terror and shame that Daphne expresses in each chapter of Kiesling’s insightful and timely novel capture this sobering sentiment exquisitely.

Jeanette Tran is a scholar of early modern literature who also enjoys reading contemporary American fiction. She currently resides in Iowa.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig