by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Picador, 2018 | 145 pages

John Keegan, historian and author of The Face of Battle – in this reviewer’s opinion the greatest military history book ever written - concludes his chapter on the Battle of The Somme with the most obvious yet difficult question of the Soldier in the First World War: “What […] was it which impelled him to leave cover, advance and engage in combat in such circumstances?” Indeed, it is impossible to learn about the experience of Soldiers in the First World War and not be struck with horror and disbelief at what they endured. Millions of young lives, drawn from an agrarian society with Victorian era values and never having seen electricity or motorized equipment, were then slaughtered by sustained long range artillery and air-cooled .50 caliber machine guns firing 500 rounds per minute. The scale of the casualties and the immensity of the battlefield were incomprehensible to early 20th century society. It was, in a sense, a global loss of innocence.

Keegan’s question leverages the moment that has come to symbolize the horror and absurdity of the First World War - the moment one is ordered to “go over the parapet,” or “leave cover.” In the outpouring of literature and historical inquiry inspired by this war, the single instant one leaves the relative safety of the trench to cross no-man’s land has become the iconic image of trench warfare. The grotesque use of death squads to execute those who refused to attack, the social divisions between the officers that ordered the attack and the men who carried them out, the hellish landscape of no-man’s land, and finally, the certain futility of the attack if one managed to make it to the enemy’s trench alive… all stretch into metaphors for a society gone mad with bloodlust. This experience has imbued the literature of the period with what Keegan calls an “eternal quality” that has never been replicated.

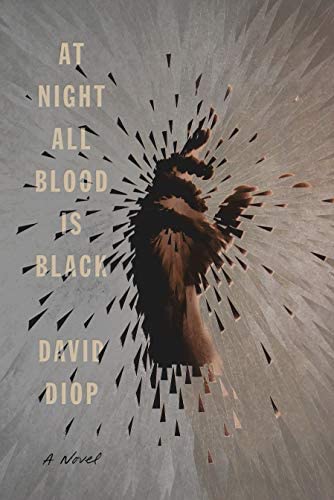

David Diop’s Booker Prize winning novel, At Night All Blood is Black, is an intensely powerful contribution to this canon. With unique perspective, visceral detail, and musical prose, Diop carves room for this piece alongside the greatest war novels ever written. The story tells of Alfa Ndiaye, a Senegalese man fighting for the French army in World War I. He is joined by his best childhood friend, his “more than brother,” Mademba Diop. When Mademba suffers a gruesome wound and dies in Alfa’s arms, Alfa begins a guilt-driven descent into madness.

The novel begins with Alfa’s lament on the memory of his friend’s gruesome death, “his guts in the air, his insides outside.” It is not the lurid image that tortures Alfa, but regret over the moment his friend asks him to “finish him off,” and he refuses. The torment sends Alfa into a spiral of self-doubt starting with the premise that he should have killed his friend out of mercy. That premise prompts him to deconstruct his moral grounding and self-image along two paths: first, on the battlefield, he seeks to understand the horror of war, the “strangeness turned to madness,” and second, through the memory of his childhood and the conditioning that produced a man capable of what he sees and does.

In the initial chapters, we read a chilling account of what Alfa does on the battlefield in response to Diop’s death. To process his regret, Alfa physically recreates the moment of his friend’s death by capturing, torturing, mutilating, and then finally, mercy killing an enemy Soldier. Narrating this horror, Alfa focuses on the final moment when the enemy Soldier – abdomen splayed and “guts in the air” – begs Alfa to kill them. He does, slicing their throat, “cleanly, humanely,” just as he should have killed his friend. He does this eight times on sequential attacks, and each time he cuts a hand off the killed enemy Soldier as a trophy. At first, the trophies he brings back earn him adulation from his fellow Soldiers for his ferocity and fearlessness. But after the fourth hand, his Soldiers and commander begin to turn; they distance themselves, aware that Alfa has crossed over into madness, not the “temporary madness” of battle, but a contagious madness Alfa describes as that of a sorcerer.

As the novel progresses, the focus shifts from the gruesome killing ritual to Alfa’s intellectual reconciliation with his own morality and the morality of war. In discovering that he should have killed his friend – something he confirms each time his captured enemy Soldiers beg for death - Alfa believes he has “reclaimed [his] humanity.” Reclamation becomes disillusionment, and Alfa sees through the false bravery of his comrades, the superficial authority of his commander, and his own absurd rationality. He discovers how “to think what I want” instead of what he has been told to think. It is here that Alfa’s commander sends him back to the rear to “rest” at a hospital for shell-shocked Soldiers.

At the hospital, Alfa’s narration becomes nostalgic and dreamlike, image-rich, and often sexual. We read his stream of conscious reconciliation of the man that left for war with the man that was shaped by the war. Instead of the cold deductive reasoning that formed his ritual on the battlefield, his thoughts at the hospital are meandering, descriptive, and carry a quality of mysticism. As compelling and captivating as Alfa’s narration is, for the reader, there remains a fundamental dissonance to the idea that Alfa discovers his humanity through gruesomely violent acts and mental disembodiment. Alfa never resolves that dissonance, but he does offer a moment of clarity in the end when he asks why, “my body […] can only bring battle, war, violence, and death. […] why can’t [it] also mean peace, tranquility, and calm?”

David Diop’s choice of narrative style adds powerful depth to the novel. Told in first-person, stream of conscious, Alfa’s narration takes on qualities of an oral history told in verse as in the bard tradition. Repeated descriptors such as “more-than-brother” to describe his killed friend and “Gods truth” as a salutation mark progress for the speaker and maintain cadence. Alfa repeats ideas as he builds towards culminating memories and realizations, as though the phrases form stairs carrying the reader or listener. This bard-like approach imbues a rhythm to the language that asks to be sung instead of read. The creative narrative style complicates the gruesome content of the novel. The song inspires the reader to sympathize with Alfa, even as we read of him mutilating and murdering Soldiers, much like an audience cheers for a singer even if the lyrics are profane.

At Night All Blood is Black is among the dozens of war novels I have written about, and hundreds of war novels I have read. David Diop’s novel transcends the oft-repeated themes and plot devices of this “eternal genre” to produce something truly unique and powerful. The chilling detail, brilliant style, and subtlety with which Diop engages a host of social and human conflicts have restoked my excitement for the future of war literature.

Adam Karr earned a B.S. in History from the United States Military Academy in 2005, and an M.A. in English from the University of Virginia in 2014. He is a Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Army with multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. Adam is currently serving as an Operations Officer in the Defense Logistics Agency.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig