by by Margaret Kolb

Published by Sylph Editions, 2018 | 185 pages

Faith. For most, it is the ‘fear of death, nothing more’. So says Father James Lavelle (Brendan Gleeson), the ill-fated protagonist of John Michael McDonagh’s 2014 black comedy film Calvary. The evidence Father James marshals are all those who lose their faith when faced with death, particularly an unexpected death. The title of the film, the place where Jesus was crucified, keeps the presence of death ominously close, and in Calvary we witness the final days of Father James’ own life, although his death is not wholly unexpected. Father James is told that he will be murdered by his killer-to-be, anonymously, in the darkness of a confessional, and is afforded a week in which to tidy up his affairs. If we accept his definition of the faith-filled, Father James is in the minority, as he does not lose his faith when confronted by death, but continues to attend to the many needs, spiritual and otherwise, of his parishioners. Thoughts of his death appear to hold no sting (although he is scarcely unmoved by the loss of others). After all, Father James is already living his own version of hell, succumbing temporarily to his addiction to alcohol in a trying week where he comforts a widow, gets beaten up, and witnesses an arson attack on his church. His navigating a public duty of care, with private, human flaws, provokes the question, can our essential goodness, holiness even, be powered by a divided identity?

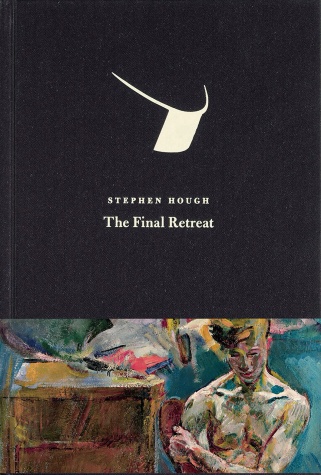

Losing faith within the shadows of death is a key theme also in The Final Retreat, the first novel from pianist and composer Stephen Hough. Here too, a Catholic priest with an addiction – an insatiable need for sex in this instance – confronts his own mortality in a linear, day-to-day chronology where death, particularly suicide, plays its part. As with Calvary, the novel’s title explicates an apt sense of ending. This is the final retreat for Father Joseph Flynn, a middle-aged, gay priest, serving a parish near Manchester in the north of England. Father Joseph has been visiting prostitutes every Tuesday afternoon for around five years. In a rare moment of guilelessness, he reveals his clerical identity to one of the men he pays. The subsequent blackmailing at this man’s hands leaves Father Joseph with little option but to confess his weekly trips to a senior cleric, whereupon he is dispatched to a residential stay at Craigbourne, Cheshire, for an eight-day silent retreat, and is instructed to keep a written record of his personal contemplations while there.

Father Joseph takes to the craft of writing with ease, and we read about him in his very frank prose as the novel unfolds through a series of first-person diary entries. He lives alone, in any case, and admits to being familiar already with ‘eccentric conversations with himself’. Since the global pandemic lockdown, we are perhaps all familiar with these, but such an isolated existence is delineated as the reserve of Catholic priests here, and Father Joseph candidly pens his account, feeling liberated at his seamless switch to handwriting from his conventional typing (computers are banned in the stark cells of Craigbourne).

Father Joseph has lost his faith. He has issues with the sixth commandment: ‘Thou shalt not commit adultery.’ He is weary of his vocation, which he describes as a ‘phantom’, a phony role he is merely playing that stands at-odds to his reality, paying for sex with men. The novel, unfolding in a series of 60 entries, each delicately titled, quickly stops being a notebook about life on retreat, and instead grows into an exploration of the deepest reaches of the man’s psyche. In the chapter ‘Jason’, we learn about Father Joseph’s first kiss; in the chapter ‘Silver Jubilee’, we learn how long it has been since Joseph’s ordination and his twenty-five years of, as he sees it, monotony, responsibility and fantasy. Here is Father Joseph’s new Rosary, with sorrowful meditations not on the events of Jesus and Mary, but on his own life and its losses, such as his father’s death by suicide, in front of his mother, on the second day of their honeymoon in Rome.

As noted, author Stephen Hough is a composer, and knowledge of his musical compositions, which include multiple works for voice, encourages the easy understanding of this progression as, at times, more of a song cycle than a novel. In some ways a precursor to the album concept – where tracks are designed to be listened to collectively and consecutively – a song cycle is a selection of individual pieces for voice, united by poetic theme or lyricist, intended to be performed in a particular order without a break. The music of the first song generally returns at the end of the work to establish a sense of completion, and The Final Retreat follows this cyclical modus operandi. It is, as mentioned, Father Joseph’s first-person account, but his story unfolds between a distinct prelude and coda - the book begins and ends with an email exchange from other voices. Moreover, there are strong thematic links between the novel and those pioneering song cycles that established the new nineteenth-century music genre in the first place. Schubert’s bleak Winterreise (1827), for example, scales the depths of despair, and, even more applicably considering the double life Father Joseph is living, the composer’s posthumous Schwanengesang (1829) features the poem, ‘Der Doppelgänger’, in which a man meets his double and is foretold of his death.

The Final Retreat is graphic. The language is brutal, and the reader may baulk at the repeated use of the f-word and the frequent, meticulous descriptions of intercourse and masturbation. At times, perhaps the expression is too gratuitous. Is it inevitable, in this context, that the old adage must be interrupted by semi-lewd parenthesis, ‘a ring (lovely word) of truth’? On the other hand, shocking language is the very honest communication of Father Joseph’s inner demons becoming public. The psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott introduced the concept of the ‘False Self’ in 1960 to describe those, often successful artists and writers, who compartmentalized a public, positive, constructed identity from a hidden, darker, wounded reality. Since Father Joseph is openly and unequivocally possessed of this – public minister and private addict – the uncompromising language asserts that little about him now remains censored, disguised or unsaid.

Despite a very personal meditation we are set up here in a world of binaries. On his drive to the retreat centre, Father Joseph contrasts his solitude with the families he imagines, and envies, residing in the houses he passes. Craigbourne itself represents to Father Joseph both old grandeur, being the former property of a wealthy merchant, but also exploitation, as it owes its existence to those destitute labourers in the nearby cotton mills. Likewise, its once plush silk and satin rooms now house plastic statues and power-saving lightbulbs, and even the wooden bannisters of the sweeping staircase are described as ‘two eyebrows’. Father Joseph’s bed stands out amongst these dualisms, ‘single (of course)’, but it is in this private space that he meets his own clerical binary. The spiritual director, Father Neville, who is a self-sacrificing, scratchy hair shirt-wearing, self-mortifying prig who visits every morning, and is, in a sense, no less obsessed with sex than Father Joseph is, proclaiming that any good a priest does means nothing if he ‘fails in chastity’. Father Neville represents that very real, very conservative side of the Catholic Church that cannot countenance a relaxation of the strict celibacy laws for priests, those who clashed with Pope Francis just this year over the possibility of ordaining married men as a solution to shortages in the Amazon region.

For Father Joseph, on the other hand, the ultimate sin is to believe that anyone could ever end up in Hell. Explicating the Old Testament story, Father Joseph asserts it utterly impossible that God actually wanted Abraham to kill his first son, Isaac. The circumstance was planned purely to engender a ‘no’ to barbarity in the Prophet’s heart, to align him with the ways of God. So too, the idea of God creating something as monstrous as Hell is one we were always supposed to refuse to accept. For Father Joseph, Christians who believe in the existence of Hell, ‘(inexplicably some people actually want others to be there)’, represent the very worst understanding of God. Admittedly, however, much like Father James Lavelle – from Calvary – Father Joseph is in his own version of hell already, although unlike Lavelle, Father Joseph regularly and readily indulges, rather than suppresses, his uncontrollable needs, crediting the very presence of an addiction as ‘energy in its purest form’. Visiting prostitutes is not a lifestyle that Father Joseph appears keen to consign to the past. Retreat or no retreat, he keeps in the present tense his description, ‘my sat nav’s memory is a record of my orgasmic history’. Father Joseph rarely repeats a visit and relies on his car satellite navigation system to arrive at a new address each Tuesday, ‘his day off’.

Yet, there is nothing negligent when the focus shifts to Father James’ ministry and scriptural knowledge. His big worry is that he does not have the spiritual strength for his parishioners. He justifies his paying for prostitutes in some cases, because these men can now, at least that day, afford to eat and support their families. In one instance, when he calls on a new man, Farhan, who is originally from Bangladesh and now living in a flat in Oldham with his wife and three children, Father Joseph’s instinct, on seeing the family, is not to go into the bedroom as planned, but to chat instead to Farhan’s wife, to find out how long she has been in the country, to join in with his children’s games. He does none of these things, but does say a prayer for the family before paying for sex with their dad. Where women feature is where we see Father Joseph at his most compassionate. There are regular references to his mother. He guiltily reflects on ‘Man’s two-minute pleasure for woman’s nine-month pain’, in an empathetic retelling of the Bible story of the woman caught in adultery, and he sensitively recalls holding the hand of the woman in a hospital bed the night before the amputation of her legs. Contrary to his own admission of his reality, Father Joseph’s life is not, in fact, lived solely as a single-minded, man-obsessed remoteness.

With its broad dualisms, fierce language, and dark themes, The Final Retreat is an arresting, harrowing and controversial personal struggle with faith and loss. Father Joseph may reject the dogma, hypocrisy and superstition, but he continues to ponder the stories, and draw on the teachings and compassion of Jesus Christ as inspiration for his own life. Indeed, the pervading theme of death is often made present through Christian characters and teachings. There are chapters headed with ‘Lazareth’, ‘Iscariot’, ‘Death and Hell’ for example. Father Joseph is disillusioned by the particularly-depressing English Catholicism, as he sees it, but, in questioning his role within it – including an apparent inability to imagine any alternative – the book is an extension of the disciple Simon Peter’s question, ‘Lord, who shall we go to’. This is a prolonged, alternative Passion, and, in a mirror to the three crosses on the hillside at Calvary, is replete with its own trinity of suicides.

Angela Moran is a freelance musician and researcher based in Birmingham, UK. After completing her PhD at Cambridge University, she published her book on music and the Irish diaspora before moving back to the city of her birth. When not playing her piano and violin, she spends her time wishing she was.

click to see who

MAKE Magazine Publisher MAKE Literary Productions Managing Editor Chamandeep Bains Assistant Managing Editor and Web Editor Kenneth Guay Fiction Editor Kamilah Foreman Nonfiction Editor Jessica Anne Poetry Editor Joel Craig Intercambio Poetry Editor Daniel Borzutzky Intercambio Prose Editor Brenda Lozano Latin American Art Portfolio Editor Alejandro Almanza Pereda Reviews Editor Mark Molloy Portfolio Art Editor Sarah Kramer Creative Director Joshua Hauth, Hauthwares Webmaster Johnathan Crawford Proofreader/Copy Editor Sarah Kramer Associate Fiction Editors LC Fiore, Jim Kourlas, Kerstin Schaars Contributing Editors Kyle Beachy, Steffi Drewes, Katie Geha, Kathleen Rooney Social Media Coordinator Jennifer De Poorter

MAKE Literary Productions, NFP Co-directors, Sarah Dodson and Joel Craig